Extra: We have an Idea, What do you think?

I’ve got an idea I would like to share with all of you readers. It’s an idea I’ve been tossing around for a while, thanks to a reader’s input, but I would like to get more opinions from more people.

The science behind the pattern

Written by: Caroline Coile, PhD

Merle in dogs is one of the most intriguing coat patterns in the dog world, both in its appearance and its genetics. Also known as dapple, merle is characterized by irregular blotches of fur set on a lighter background of the same pigment, such as solid black on gray (called blue merle) or solid brown on tan (red merle). Blue and partially blue eyes are often seen with the merle pattern, as well.

Although beautiful and unique, this color can also be associated with health problems, primarily deafness and blindness. Awareness is key to responsible breeding; it is not recommended to breed two merles together.

There are several merle dog breeds where the pattern is commonly found and accepted as a breed standard, including:

Research shows that the gene responsible for merle in dogs is the same in every breed, indicating that it is an ancient mutation that predates the formation of dog breeds. It is unlikely to have arisen independently in different breeds.

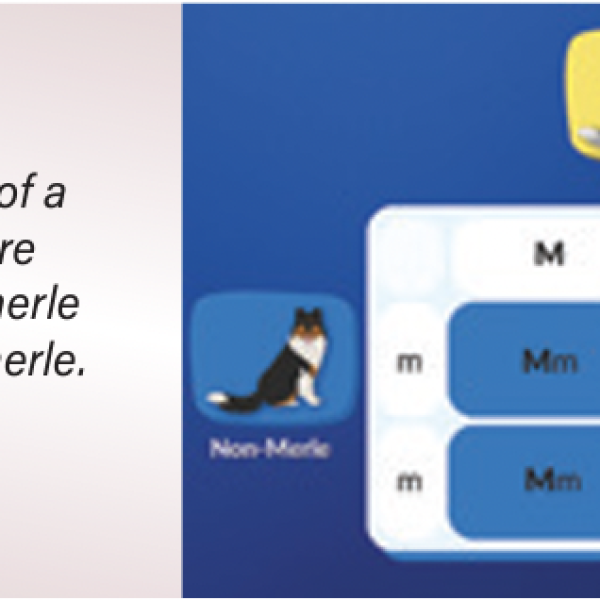

The merle coat color lies in basic genetics, where there is a dominant and recessive trait to produce those gorgeous splotches. This is the merle allele (M) and one copy of the non-merle allele (m). The merle (M) allele is a semi-dominant gene, meaning it only takes one copy of the M allele to produce a merle. So, every merle dog has one copy of the merle allele (M) and one copy of the non-merle allele (m), meaning every merle dog has an Mm genotype, and, therefore, every nonmerle dog has an mm genotype.

The merle allele was first discovered at Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine in 2006. The merle coat color is governed by a type of mutation called a SINE insertion in the SILV (also called PMEL17) gene.

What about dogs with two merle alleles (MM)? These “double merles” (or “double-dapples”) don’t look like merles.

What about dogs with two merle alleles (MM)? These “double merles” (or “double-dapples”) don’t look like merles. They usually have much more white on them—and some can be almost pure white. The fully pigmented splotches are much smaller, and the background color is much whiter.

The merle pattern can lead to a slew of health problems. The most common is hearing loss in one or both ears. Having even a single M allele actually raises the chance of being deaf, although the chance of an Mm merle being bilaterally deaf is still less than 1 percent. The presence of two M genes, however, greatly increases the chance of deafness, depending on what breed it’s in. For example, in one study, about 10 percent of MM Catahoula Leopard Dogs, about 56 percent of MM Australian Shepherds, and about 85 percent of all other MM dogs studied were deaf in both ears.

Double-merle dogs also often have microphthalmia, in which the eyes are abnormally small (sometimes barely there) and often nonfunctional. They may also have abnormal pupils. Researchers don’t yet know why any of these abnormalities are associated with double merle; possibly it’s because the merle mutation affects ByCaroline Coile,PhD • Australian Shepherd • Miniature American Shepherd • Collie • Shetland Sheepdog • Dachshund • Cardigan Welsh Corgi • Pyrenean Shepherd • Great Dane • Mudi • Catahoula Leopard Dog • Chihuahua • Border Collie • Pomeranian Anexampleofa punnetsquare betweenamerle andanon-merle. melanocytes, the cells that produce melanin pigment, and melanocytes are found not only in the skin but in the eye and inner ear, as well as the bones and heart.

Regardless, it’s best to avoid breeding a merle to a merle. Because both parents will have the Mm genotype, on average only half the offspring will be merle (Mm). More importantly, you’re likely to produce a quarter that are double-merle (MM).

Although not all double-merles have auditory or visual problems, it’s best to avoid taking the chance. That sounds simple enough: Just don’t breed two merles together. The problem is that not all merles are obvious, such as “hidden” merle and “cryptic merle.”

In hidden merle, the merle pattern is hidden by the action of genes at another location. The recessive “ee” genotype inhibits the expression of any dark pigment, including the dark pigment in merles. If a dog were Mm and ee, it would just look cream or red in any pigmented area since the merle mutation only affects dark pigment. In cryptic merle, the merle pattern is expressed only in very small areas, so small you might not notice them unless you searched the dog’s entire body for a trace. But these dogs can also carry the M allele and may produce merles as well.

That’s why it’s essential to DNA test before you breed any dog from a breed or family known to produce merle. A DNA test can tell you if your dog has zero, one, or two M alleles.

As you can see, while the inheritance of merle in dogs seems simple at first, it can get pretty complicated. Fortunately, you don’t really need to know any more about the science to appreciate its beauty and to make wise breeding decisions.

You may notice that some dogs only have the merle pattern on their face, for example, while others show splotches on their entire body. There’s some additional science behind that. The SILV gene involved with merle in dogs is responsible for producing a matrix that essentially holds the pigment in place. In a non-merle dog, the matrix is completely formed and pigment stays put. But if one SILV allele has this insertion of extra genetic material in it, the matrix has holes in it. Pigment granules escape from the holes, leaving a faded coat color.

However, the length of this genetic insertion is not very stable, and as cells divide during embryogenesis, which is the process of the development of an embryo, it may shrink or expand. In some embryonic cells, it shrinks to the point of being nearly normal, and the matrix these cells produce is almost complete. During development, cells derived from these nearnormal embryonic cells give rise to patches of the fully pigmented coat.

Thus, merles are a mosaic of copies derived from cells with various degrees of “leaky” matrixes and normal matrixes. The size of each patch depends on how early in embryogenesis the insertion size mutated, with larger patches descended from earlier mutation events.

Merle is a complicated and fascinating color pattern—both in appearance and in genetics. That’s why dog breeders and geneticists alike consider merle in dogs beautiful.

I’ve got an idea I would like to share with all of you readers. It’s an idea I’ve been tossing around for a while, thanks to a reader’s input, but I would like to get more opinions from more people.

The welfare of animals in commercial dog breeding facilities is a matter of great concern for animal rights activists, government agencies, and responsible breeders alike. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) plays a pivotal role in ensuring that these facilities meet stringent standards to guarantee the wellbeing

of the animals in their care. However, the

proposition of commercial dog breeders wearing

body cameras during USDA inspections has

sparked a significant debate. In this article, we

will explore why this approach may not be the

most effective way to promote animal welfare

and advocate for a cooperative relationship

between breeders and the USDA.

In January of 2024 AKC released an email welcoming these smart, sturdy, compact dogs as an officially recognized AKC breed, the 201st, actually. According to the AKC, this breed has been around for quite some time in London and abroad, and in 2003, the breed was placed on the Endangered Breeds list of The Kennel Club, U.K, due to the small number of dogs composing the gene pool and the risk of several inherited diseases.